It is widely regarded that The Graduate marked the beginning of countercultural consciousness in American movies. In the fading memory of that moment, now layered with so many ironic reversals, retrenchments, and disappointments, it is less the film that is recalled than the potent effect it produced. Shorn of its contemporary context, Nichols’s film is a nicely executed comedy of romantic embarrassment spruced up with Felliniesque close-ups.

The movie that finally breached the already crumbling fortress of old Hollywood was Dennis Hopper’s 1969 bombshell, Easy Rider. In Easy Rider, the fabled ‘road' equals freedom, befouled by ugly Americana. But in Monte Hellman’s 1971 classic, Two-Lane Blacktop, it becomes something altogether different and far more interesting: a repository of dreams and fantasies, for squares, hipsters, and obsessives alike. Where Hopper’s film is set in the Great American Dreamscape, Hellman’s vision of the American West is far less pretentious, parcelled out in nicely measured, seemingly offhand portraits. Where Hopper wears his hipster credentials on his sleeve, Hellman obscures his and even tones down his well-made soundtrack choices in the mix. Where Hopper and Fonda “play” disenchantment and disaffection (offset by Nicholson’s authoritative charm), James Taylor, Dennis Wilson, and Laurie Bird are three non actors who embody a sense of youthful restlessness (offset by Warren Oates’s heartbreakingly eloquent woundedness). And where Easy Rider is finally a series of choices and strategies and inventions clustered around a big concept, Two-Lane Blacktop is a movie about loneliness, and the attempts made by people to connect with one another and maintain their solitude at the same time—an impossible task, an elusive dream.

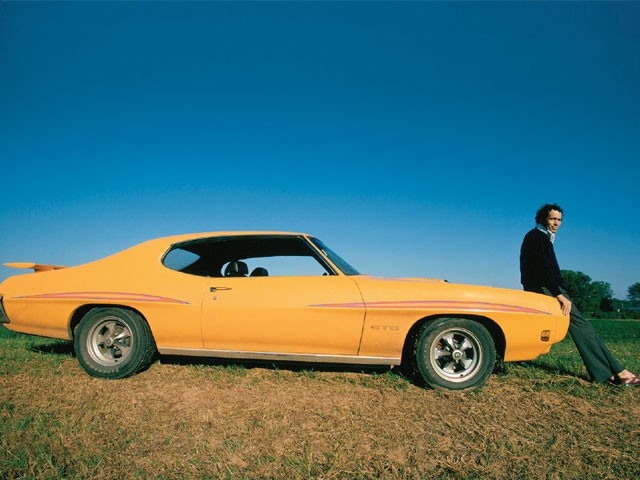

The rough cut of Two-Lane Blacktop was three and a half hours long. “We were contractually obligated to deliver a two-hour movie, so we lost half the script,” said Hellman. “We lost some good scenes, for sure, that I fell in love with.” Gone are the flavour and colour of street-racing life and the road, evoked so beautifully in Wurlitzer’s script. What is gained is a trancelike absorption in movement and ritual. Hellman’s film is composed of many of the in-between moments that most filmmakers would cut. In the process, a strange terrain of tenderness and disconnection inhabited by the four principal characters is mapped out: their shared remoteness is exactly what makes it safe for them to venture into one another’s company. This movie about a cross-country race between a car freak in a lovingly souped-up ’55 Chevy and a fantasist in a store-bought GTO moves at an even, gliding pace, and it’s all about stopping to gas up, eat, make some bread in local quarter-mile drag races, pick up hitchhikers, let the engine breathe, share a drink.

Though he visually reads ‘hippie’, Taylor is the classic introvert, for whom everything is swallowed up and contained by the road. Oates is the smiling extrovert-dreamer, for whom everything becomes a part of the Playboy dream he’s spinning on his drive across America. Wilson provides the authenticity of a genuine drag racer and car fanatic who oozes the Californian dream. Taylor’s aquiline face may be the visual center of the movie, buoyed by Bird’s pout and Wilson’s West Coast stoned softness, but Oates is its emotional core. Oates’s nameless would-be hipster is perfect in every way: V-neck sweaters (they keep changing colour), driving gloves, a wet bar in the trunk, music for every mood, a cocky grin that looks like it’s been practiced in the mirror. The actor imbues his character with a strong sense of physical uneasiness—he can’t even lean against a building comfortably.

Unlike Oates’s GTO, who projects his desperate longing out onto the open spaces, for Taylor’s Driver the road is a refuge. Or perhaps a cocoon. The nihilistic tone achieves grandeur in itself, up to the controversial and bravura finale. “It was really the most intellectual, conscious manipulation of the audience that I’ve ever done,” said Hellman. “I thought it was a movie about speed, and I wanted to bring the audience back out of the movie and into the theatre, and to relate them to the experience of watching a film. I also wanted to relate them to, not consciously but unconsciously, the idea of film going through a camera, which is related to speed as well. I think it came to me out of a similar kind of thing that Bergman did with Persona.” Hellman is literally arresting his character’s fantasy of dissolving into pure speed and limitless road (the burn of the image begins in Taylor’s head), a fantasy shared by countless movies, then and now. Including Easy Rider.

Two-Lane Blacktop is the least romantic road movie imaginable. Nonetheless, Hellman saw it as a romance. In finished form, it is ultimately a great film about loneliness and self-delusion. Warren Oates’s GTO (as he’s credited) is every pontificating drunk, every reformed junkie, every guy who moves to another town to begin again. “We’re gonna go to Florida,” he tells Bird in the film’s most acutely poignant moment. “And we’re gonna lie around that beach, and we’re just gonna get healthy. Let all the scars heal. Maybe we’ll run over to Arizona. The nights are warm . . . and the roads are straight. And we’ll build a house. Yeah, we’ll build a house. ’Cause if I’m not grounded pretty soon . . . I’m gonna go into orbit.” Meanwhile, she’s ready to doze off in the passenger seat. Like all dreamers, he’s just talking to himself.