Native service presents a paradox to non-Natives. Why would they fight for America, which has a long history of colonising, massacres and breaking treaty promises? As in other communities, military service is viewed as an honourable tradition by many Native families and tribes. And Native people join for the same reasons as anyone else - to learn a trade, get an education, experience the thrill of piloting a jet, explore new life horizons, strike a blow for gender equality. However, for most it is also a way out of desperate poverty.

The history of service for many Indigenous people is tied to their love of homeland—which, after all, was theirs long before colonists ever appeared. Some Natives also believe it is their duty to defend America as a manifestation of fulfilling treaty obligations. For Native Hawaiians, military service fits into the traditional concept of aloha—which includes mutual support and mutual cooperation, Staff Sergeant Thomas Kaulukukui's father and 11 siblings served during World War II, and he was drafted to fight in Vietnam. “We must serve when needed,” Kaulukukui said. A Vietnam veteran said that even though the U.S. had broken its treaty promises, “we are more honourable than that. [We] honour our commitments, always have and always will.”

The large number of Native people serving during World War II lead to a resurgence of tribal practices—such as protection ceremonies, prayer vigils and carrying of tribal medicine into battle. The Lakota from the Standing Rock Reservation held the first Sun Dance in 52 years, to pray for the destruction of German and Japanese soldiers and the safe return of 2,000 of their soldiers. Research suggests that Native Vietnam veterans may have better coped with anger, depression and post-traumatic stress thanks to “tribal rituals connected with warfare and/or ceremonies of healing.” Going away and coming home ceremonies are still practiced, including honouring ceremonies and victory dances, say Harris and Hirsch. For Native Hawaiians traditions that can include hula, surfing, art and songs to commemorate various battles can help with healing and restoration. Powwow celebrations, social dances and other veterans’ events—held year-round in Indian Country and in cities and towns across the nation—broaden the support. But, as minorities, Indigenous peoples have unique struggles.

Native Americans—a group that includes American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians—have served in U.S. conflicts since colonial times. Tales of individual soldiers and units have long been known to historians, the military and families. Native people in the South were often lumped in with what was then described as “coloured” units. And, when the Selective Service Act was passed in 1917, which led to the draft, it was unclear to the military how to handle enlistment of American Indians who were not U.S. citizens—about a third of the Indian population at the time. During the Vietnam War, for example, the military did not use the ethnic category “Native American.” Recruiters often used other descriptions, including “Mongolian,” “Negro,” “Latin” or “Spanish,” with some Native Americans also being described as “Caucasian.” It’s estimated that 1.4 percent of all troops in Vietnam were Native American, at a time when they represented 0.6 percent of the U.S. population. The scholars estimate that up to a quarter of adult American Indian men served in World War I. During World War II, 44,000 served, with another 800 women working in various capacities. Some 10,000 served in Korea and approximately 42,000 in Vietnam.

For some Native Americans, joining the U.S. military gave them an opportunity to continue a warrior tradition, especially during the Civil War and the late 19th century, when the U.S. government was bent on assimilating or exterminating American Indians. Native Americans were enlisted—and given military pay—as scouts to help find tribes that were doing their best to defend themselves against encroaching settlers. The U.S. Army believed that having scouts from the same or related tribe would destroy morale and facilitate surrender. Sometimes Indians worked as a type of hired contractor. “They were eager to wage war against a common enemy,” say Hirsch and Harris. Whites were powerful allies. In 1876, Crow and Shoshone men went to battle with U.S. General George Crook against the Sioux—a traditional enemy. Osage led U.S. military expeditions against the Comanche and Kiowa. Thus, serving as a scout was a means for continuing a way of life when the U.S. government was trying to stamp out their traditions, says Hirsch. But some may also have viewed their service as a tactic for preventing the Army from wiping out their people. The federal government outlawed Native American traditions as part of its assimilationist push. But military service afforded Indigenous people a way to covertly or even overtly get back to some of those practices.

Master Sergeant Woodrow Wilson Keeble (Dakota Sioux), who served in both World War II—notably at Guadalcanal in the South Pacific—and Korea, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Purple Heart, the Bronze Star, and in 2008, 26 years after he died, the Medal of Honor. In Korea, Keeble launched a one-man assault against a line of Chinese-held bunkers manned by machine gunners. Armed with an automatic rifle and a bunch of hand grenades, Keeble destroyed all the bunkers on his own, paving the way for his unit to seize the hill. Keeble later became disabled by his war wounds—including from 83 grenade fragments that had to be removed after that assault. But he was still active in veterans’ events and causes.

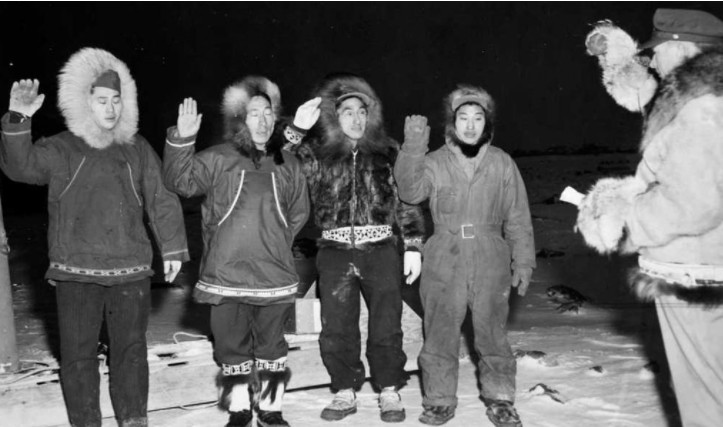

The Alaska Territorial Guard (ATG), a band of some 6,300 Natives, ranging in age from 12 to 80, served as the military’s eyes and ears along the 6,640 miles of the territory’s coastline during World War II. Alaska was highly segregated at the time and Natives were paid less than half of what whites made for the same work. That led to concerns that they might not be the most reliable allies. As it turned out, there was nothing to worry about; Alaska Natives were very reliable. The ATG shot down Japanese balloon bombs that were traveling on the jet stream—that role and those weapons were classified until long after the war. The existence of the Guard also laid the groundwork for racial equality.

Born in a tipi on the plains of southwestern Oklahoma, Horace Poolaw (1906–1984) endeavoured to be a photographer from the time he was a teenager. He left school after the sixth grade and apprenticed himself to professional photographers in his hometown of Mountain View in order to learn the trade. The young Kiowa man succeeded in documenting his multi-tribal community from the 1920s to the 1970s. They also record his great interest in the military, both the warrior traditions of his tribe and the personal service of himself and his family. One of the most frequent faces in Horace Poolaw’s photographs of military events was First Sergeant Pascal Cleatus Poolaw, Sr. He has been called the most decorated American Indian serviceman in the history of the United States military, and was also a member of the Black Legs Society. Sgt. Poolaw’s service spanned three wars – World War II, Korea and Vietnam – and earned him 42 medals, badges and citations, including four Silver Stars, five Bronze Stars, three Purple Hearts (one in each war) and the Distinguished Service Cross.

Although Sgt. Poolaw had retired from the military, he reentered in 1967 hoping to prevent his son Lindy from having to deploy. (Army regulations prevented two family members from serving in the same combat zone without their consent.) Another son, Pascal Cleatus, Jr., had recently returned from Vietnam after losing a leg. Sgt. Poolaw’s strategy failed, and father and son went to combat together. This was not new for Cleatus, however, who had served in World War II with his father Ralph (Horace’s brother), and two brothers. Four months later, he was killed while carrying a wounded soldier to safety. Horace greatly admired his nephew Cleatus, and after his death the photographer committed his energy to seeing him inducted into the Hall of Fame of Famous American Indians in Anadarko, Okla., where a bust of him now resides.