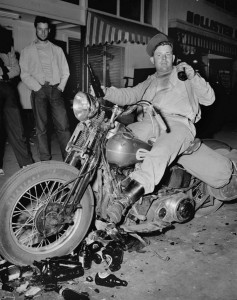

Here was a figure to strike fear into the heart of war-weary America — a bleary-eyed, beer-bellied hoodlum, surrounded by residue of a binge, empties at his feet, a bottle in each beefy fist. But what many found the most terrifying was his throne — a Harley Davidson motorcycle.

The picture ran on July 21, 1947, in Life Magazine, the place where, before television and tweets, people went to get a glimpse of what the rest of the world was up to. On that day, readers learned about a “Cyclist’s Holiday” as Life called it. A short caption told of a three-day nightmare, when an estimated 4,000 two-wheeled terrors rolled into the sleepy California town of Hollister, best known for its production of garlic, to attend a motorcycle rally over the Independence Day weekend. What happened there would go down in history as the Hollister Motorcycle Riot.

This is how Life described it: “Racing their vehicles down the main street and through traffic lights, they rammed into restaurants and bars, breaking furniture and mirrors. Some rested awhile by the curb. Others hardly paused. Police arrested many for drunkenness and indecent exposure but could not restore order. Finally, after two days, the cyclists left with a brazen explanation. ‘We like to show off. It’s just a lot of fun.’ ”

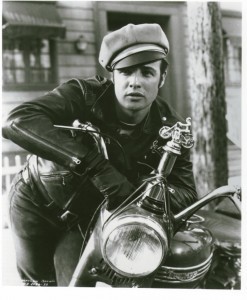

The incident captured the imagination of fiction author Frank Rooney. In January 1951, Harper’s Magazine published “The Cyclists’ Raid,” Rooney’s short story of a motorcycle gang occupying and wrecking a small California town. That story, in turn, caught the eye of filmmaker Stanley Kramer. Two years later, it came to the screen, starring bad-boy heartthrob Marlon Brando. “The Wild One” was about a “gang of hot-riding hot-heads who ride into, terrorise, and take over a town,” as the film’s trailer put it. Brando gave a face, and a wardrobe, to a new American anti-hero, the motorcycle outlaw. Suddenly, every schoolboy had to have the black leather motorcycle jacket that Brando wore as he perched upon his Harley. The jacket became so closely linked to the burgeoning rebel-without-a-cause culture that it was banned in many schools around the country. In one of the more memorable scenes from the movie, Brando gives the new underclass icon his motivation.

“Hey, Johnny, What’re you rebelling against?” a girl playfully asks him.

“Whaddya got?” he says with a world-weary smirk.

It launched a movie genre, and more motorcyclists-mostly WWII veterans having a hard time coming home — put on leathers and took to the road. In his book, “Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga,” journalist Hunter S. Thompson summed it up: ‘The concept of the ‘motorcycle outlaw’ was as uniquely American as jazz. Nothing like them had ever existed.” And all of this came about because of a riot in a tiny California garlic-farming town on that July weekend.

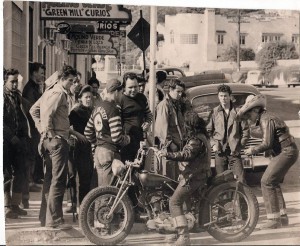

Or did it? To this day, no one can say with any certainty exactly what happened in Hollister. The town had been the site of motorcycle rallies, wholesome stuff like races and hill climbs, during the 1930s. After the war, the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) revived the tradition with an event called the gypsy tour, set for the first weekend in July. They were expecting 1,500 riders. An estimated 4,000, equal to the population of the town, roared in, although some say the number was closer to 2,000. Whatever the figure, there was no disputing that the town was overrun, far more than the seven-man police force could handle. Many came from rough-and-tumble clubs like the Boozefighters and the Pissed off Bastards of Bloomington, the group that evolved into the Hell’s Angels. What happened next was, noted the San Francisco Chronicle as “the worst 40 hours in Hollister’s history.” Leather-clad toughs zoomed through town, performing wheelies on manicured lawns, flinging beer bottles, fighting, and urinating in the streets, driving their bikes right into the bars.

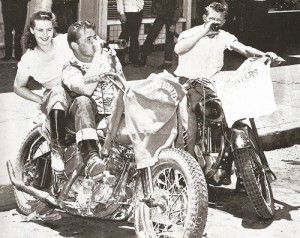

On Sunday night, the California Highway Patrol came to help. By Tuesday morning, the drunken bikers were gone and things went back to normal. Just a few months later, the town was happy to host another rally. The riot may well have been forgotten, had it not been for the photograph taken by a San Francisco Chronicle lensman. One story goes that the photo was faked, that the photographer grabbed the first drunk he could find and set him up on the bike, but some questions remain about that, as well. The photo eventually made its way into Life, and then into folklore. American outlaws had taken the leap from horses to Harleys.

Motorcycling’s rough element started calling themselves “one percenters” and wearing patches announcing this status. It’s a reference to a comment made after Hollister that 99 percent of motorcycle riders are law-abiding citizens and that the troublemakers represent the minority. The phrase is widely attributed to the AMA, but the association denies it. Hollister continued to host motorcycle races and at one, the 50th anniversary of the riot in 1997, the promoters invited back one of the original 'Wild Ones' - 76-year-old Wino Willie Forkner, leader of the Boozefighters and said to be a model for Brando’s character.