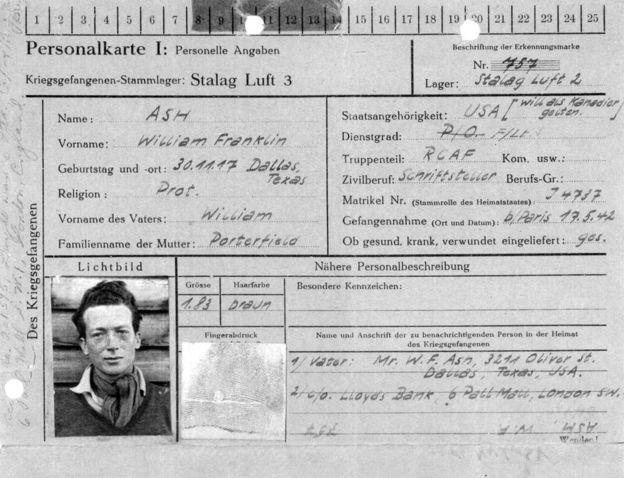

World War Two conjured up many extraordinary characters. But even among the most exalted company William Ash - the model for the Vergil Hilts character played by Steve McQueen in The Great Escape - stands out. Ash was an American who, while his country was still reluctant to enter the war, crossed into Canada to train as a pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was posted to Britain and flew Spitfires with RAF 411 Squadron.

In March 1942 he was shot down over northern France but escaped from the wreckage of his plane and was given shelter by a number of courageous French women and men. He was captured in Paris by the Gestapo and condemned to death. His life was saved by the Luftwaffe who argued that as an airman, Ash was their prisoner. He spent the rest of the war in various Prisoner of War camps. But instead of being grateful for his salvation he became an obsessive "escapologist" - seeking to break free by whatever means came his way.

Ash always modestly denied the claim he was based on McQueen's character. For one thing he didn't ride a motorbike, he said. For another, he did not take part in the breakout from the Stalag Luft III camp, on which the movie is based. The reason he did not participate in that particular breakout was that he was locked up in the "cooler" - as the camp jail was called - as punishment for a previous escape attempt. In actuality, Ash was every bit as charismatic as the fictional Hilts with whom he shared many characteristics. Apart from being American, he was good looking, dashing and more than a bit of a rebel. He was also delightfully self-deprecating. He described some of his exploits in his writings, though he often underplayed his sufferings and achievements.

He had a tough upbringing in Depression-hit Texas where his father struggled to bring up a family on what he made from his job as a travelling salesman. Young Bill worked his way through university but could find no job at the end of it and spent months riding the rails as a hobo, seeking whatever work he could get. His experiences shaped his political views. He was too young to join the idealistic Americans fighting Franco's nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. But when World War Two broke out, he was determined to do his bit to combat fascism.

It rankled with him that he did not do more fighting. He only managed to shoot down one German aircraft for certain before he was downed himself. He decided to use his incarceration to wage war on the enemy by other means. Most of his fellow inmates had little interest in escaping. Having survived the trauma of being shot down, the majority decided they had used up their store of luck and tried to pass the time behind the wire as best they could, often studying and acquiring new skills, while they waited for the war to end.

Bill Ash belonged to a hard core devoted to overcoming every obstacle the Germans put in their way to returning home and carrying on the fight. They often found it hard to analyse precisely their motivations. Some felt it was their duty. For others, focusing on a project was a way of combating the stultifying boredom. In Bill's case it boiled down, he said, to "an unwillingness to crawl in the face of oppression".

He lost count of his escape attempts, or the number of times he was condemned to a spell in the 'cooler', which meant solitary confinement and a bread and water diet. Some of the escape bids were opportunistic efforts like the time he wangled his way on to a work detail tasked with unloading a train then made a run for it when the guards' backs were turned.nOthers were complex, long-term schemes that required a huge amount of organisation, ingenuity and endurance. A little-known but extraordinarily ambitious project was the Latrine Tunnel Escape which took place in Oflag XXIB, a camp near the Polish town of Szubin.

Bill had a hand in devising the plan, which was not for the faint-hearted. It involved digging a tunnel more than 100 yards long from a starting point beneath a large lavatory block. Every day for three months teams of diggers would lower themselves through a trap door set into a toilet seat trying to avoid falling into the lake of raw sewage beneath. An entrance set into wall of the latrine pit led into a chamber where the tunnel began. Day after day they would scrape away at the sandy soil working by the light of margarine lamps. They lived in fear of cave-ins and asphyxiation and panic attacks brought on by claustrophobia. Tunnelling was in some ways the easy part. To stand any chance of making it out of Nazi-controlled territory they needed civilian-style clothing, money, and documents. Here they were helped by other prisoners who brought a wide variety of skills either acquired in peacetime or learned in the camp.

Eventually, one night early in March 1943, 35 men dressed in outfits fashioned from Air Force uniform and blankets and armed with convincingly forged identity cards crawled through the narrow tunnel and under the perimeter fence to freedom. One managed to get as far as the Swiss border before being recaptured. Two made it to the Baltic and were on their way in a rowing boat to neutral Sweden when they disappeared, presumed drowned. All the rest were recaptured within a few days. It was a bitter disappointment, but almost all carried on trying to escape. Bill finally succeeded a few days before the war ended, breaking out of a camp near Bremen just as the British Army arrived.

His experiences as a prisoner had a profound effect on his political outlook. After the war he stayed on in Britain and seemed set to follow some of his camp comrades - like Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer Tony Barber and TV presenter and historian Robert Kee - into a successful conventional career. He went to Oxford University and joined the BBC, which gave him a top administrative job in India. His increasingly radical views made it hard for him to conform, however. He rejected the Communist Party of Great Britain as being too compromised and helped found a breakaway group. He also lost his full-time job with the BBC, though he continued to do some work for the drama department.

Ash was a happy and gregarious man who never lost a touch of his boyhood innocence. His career as an escapologist showed him that in wartime people were capable of extraordinary selflessness. Why was it, he wondered, that this spirit could not be carried on into peacetime?