Motorcycle’s and black leather jackets are synonymous today, but it wasn’t always that way. The majority of the early leather motorcycle jackets were adapted from aviation and military gear following World War I. During this time, leather jackets were associated with speed and adventure. Interestingly, it was Hollywood and the movies that gave the motorcycle jacket its enduring mystique.

‘‘The Wild One’’ shaped a creed of cool that has never really aged and it's iconography of the motorcycle jacket still resonates today. Brando’s 1950 Triumph Thunderbird 6T riding 'Johnny' instigated this social revolution — until then most notable as the protective gear of highway patrolmen — the motorcycle jacket became an institution on the strength of the way he wore it. Together they made the ultimate Sign — where the signified and signifier were equal in power. A look swiftly mimicked, cloned, spoofed, appropriated by fashion and silk-screened by Andy Warhol in a series of works that constituted its sanctification. In ‘‘Four Marlons,’’ Warhol printed one still in quadruplicate on a raw linen canvas evocative of gold. Here was a personality to build a cult around.

Two years later, “Rebel Without a Cause” staring James Dean, was released. The film and Dean’s subsequent death in an auto accident, sealed the connection, in the public mind, between speed, danger, rebellion, and the black leather motorcycle jacket. The movie’s success ushered in an era where the motorcycle and the leather jacket began to be identified with the rebellious youth, especially in America.

Just as actual 1930s gangsters aped the style of characters played by the actor George Raft, real-life delinquents turned to black leather. You didn’t need a motorcycle to be in a ‘‘motorcycle gang,’’ according to the moral-panic logic of the day. What is more, you didn’t even need a gang to enjoy the aura of a gangster, a fact attested by the many teenage rebels whose acquisition of a motorcycle jacket constituted the full extent of their rebellion. But for the fashion subcultures — that is, for rock bands and teen cliques devoted to them — the motorcycle jacket is an international uniform impervious to becoming obsolete. It is a garb for all tribes: from goths in Iceland to rockabillies in Japan.

Writing about the Ramones, the critic Tom Carson once sketched the dynamics of the masquerade: ‘‘Their leather jackets and strung-out, streetwise pose weren’t so much an imitation of Brando in ‘The Wild One’ as a very self-conscious parody — they knew how phoney it was for them to take on those tough-guy trappings, and that incongruousness was exactly what made the pose so funny and true.’’ The Ramones’ imitators did not necessarily get this, and instead, reading the self-parody as an uncomplicated statement of force, copied that.

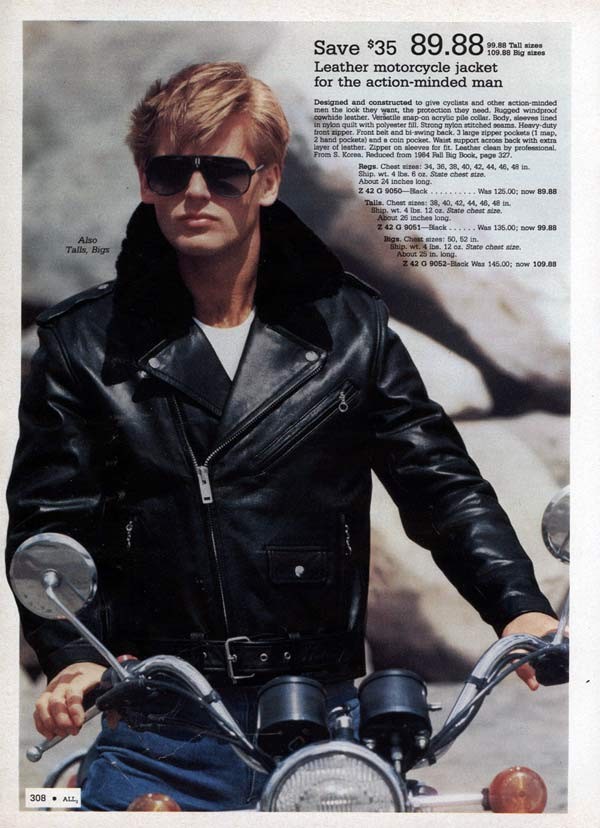

While Brando's motorcycle jacket was eventually appropriated by fashion and taken down some terrible avenues (especially during the 1980's), other motorcycle jacket silhouettes fared better. As style conscious 50's teens embraced the classic Brando jacket, actual motorcycle riding apparel manufacturers including Langlitz, Buco and Beck among others, pushed forward during this time creating new innovative styles based around real functionality and protection. One of these styles was the now classic J-100 by the Joseph Buegeleisen company in Detroit Michigan, a sleek and less bulky jacket, the form and cut is one of the most flattering of all cafe racer designs ever produced. Made specifically for racing, the full-piece panels and tubular sleeves make the garment appear very aerodynamic. The extra body length, with high mounted zip allows the rider to sit down without stressing the garment around the hips, but still keeping the lower back covered when riding.

These futuristic jacket silhouettes ushered in a new era of motorcycle style and continued in popularity through the 1960's into the 70's with the Cafe Racer being immortalised by Peter Fonda in the movie Easy Rider.

Click HERE to view the new ELMC J-100 Cafe Racer reproduction