In autumn 1940, a small group of Native American Chippewas and Oneidas joined the Thirty-second Infantry Division for the express purpose of radio communications. Soon afterward, an Iowa National Guard unit, the Nineteenth Infantry Division, brought several members of the Sac and Fox tribes into its ranks for the same purpose. Their training, and their use in maneuvers in Louisiana, hinted at the successful utilisation of Indians as combat radiomen.

The tactic seemed so promising that the Thirty-second requested the Indians' permanent assignment to the division, and the army expanded the program in 1941. With posts in the Philippines, where Spanish was commonly spoken, radiomen were needed who could transmit messages directly to the Filipino forces, to American units, and if needed, in code.

The War Department found among the Pueblo Indians the necessary linguistic abilities, actively recruited them into the New Mexico National Guard, mobilised the outfit, and shipped the unit to the islands. Optimism prevailed within the Signal Corps, and, in spring 1942, thirty Comanches entered the Signal Corps and were dispatched to the European Theatre.

Despite the army's early efforts and the proficiency demonstrated by Indian code talkers, the War Department never fully grasped the program's potential. No more than a few dozen Indians were trained for radio operations. In contrast, the US Marine Corps developed the concept on such a broad level that it became an integral part of the branch's combat operations. Unlike the army, Marine solicitation of Indians did not commence until after Pearl Harbor. Moreover, the program resulted not from within the military but from a civilian source.

In February 1942, Philip Johnston approached Major James E Jones, Force Communications Officer at Camp Elliot in San Diego, with a plan to use the Navajo language for battlefield radio transmissions. Johnston had lived among the Navajos for more than 20 years and during that time had become fluent in their language. He explained that Navajo spoke a language unlike any other Indians and added less than a dozen anthropologists had ever studied that part of Navajo culture. Even German scholars who visited Indian communities in the 1930's, including Nazi propagandist Dr Colin Ross, ignored the Navajo language. In essence, this peculiar language seemed safe from enemy understanding if incorporated into the Marine Corps' communication structure.

Johnston convinced Major Jones of the possible worth of his idea, and before the week's end, the Marine Corps extended Johnston the opportunity for a demonstration. On the morning of February 28, the former missionary's son and four Navajos arrived at Camp Elliot.

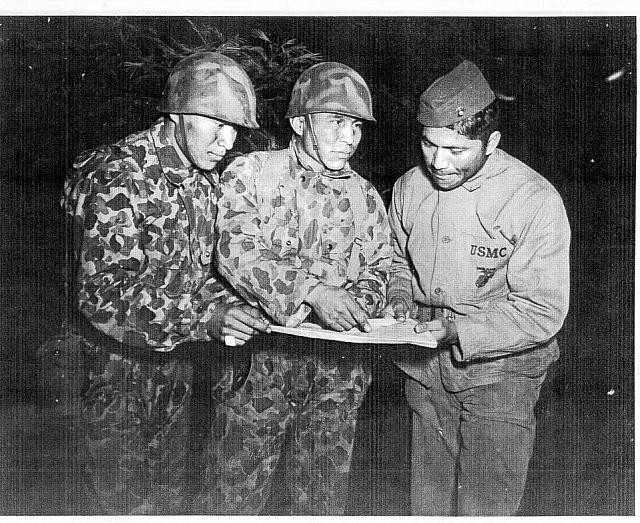

Major Jones gave them six messages normally communicated in military operations and instructed the group to assemble forty-five minutes later at division headquarters. With such a short time to devise a basic code, the Navajos worked feverishly. At 9:00 A.M. Johnston and the four Indians appeared before Jones, General Clayton B. Vogel, and others to conduct their demonstration. Within seconds, the six messages were transmitted in Navajo, received, decoded, and correctly relayed to Major Jones.

"It goes in, in Navajo? And it comes out in English?" questioned one rather surprised officer. In later tests, three code experts attached to the United States Navy failed to decipher "intercepted" transmissions; the system "seemed foolproof." Both Jones and Vogel were immensely impressed.

Over the following days, the merits of an Indian code-talking program gathered interest with General Vogel's staff. By mid-March, the Marine Corps authorised the recruitment of twenty-nine Navajos for communications work and formed the 382nd Platoon for the Indian specialists. Immediately, the boarding schools at Fort Defiance, Shiprock, and Fort Wingate received visits from marine personnel, and the original complement of code talkers was formed. In addition, Philip Johnston petitioned the Marine Corps for his own enlistment as training specialist at a noncommissioned rank. Though already in his forties, the Marine Corps accepted his offer.

The Indian recruits received basic training and advanced infantry training in San Diego before they were informed of their particular task. To a man, the Indians responded enthusiastically and began the construction of a code. Once the first 29 were trained, two remained behind to become instructors for future Navajo code talkers and the other 27 were sent to Guadalcanal to be the first to use the new code in combat.

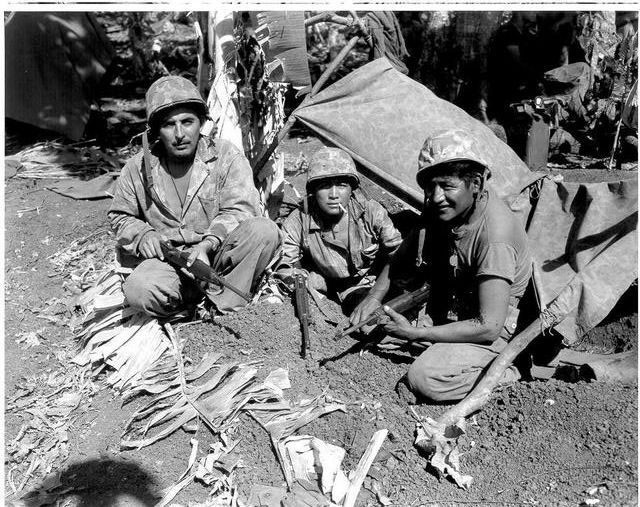

In jungle combat in the Pacific, the Navajos' innate strength, ingenuity, scouting and tracking ability, habitual Spartan lifestyle, and utter disregard for hardships stood them in remarkably good stead. At first utilised usually only at the company-battalion level, the Navajos became virtually indispensable as their capability and reliability were recognised.

Frequently, and especially when a Marine regiment was fighting alongside an Army unit, the Navajos' physical resemblance to the Japanese led to confusion that resulted in several Navajos almost becoming casualties of 'friendly fire' by their fellow-Americans. Many Navajos actually were captured and taken for interrogation. One such Navajo, William McCabe, was looking for something to eat while waiting on a Guadalcanal beach for his transport ship. 'I got lost among the big chow dump,' he recalled, 'All of a sudden I heard somebody say, `Halt,' and I kept walking. `Hey, you! Halt, or I'm gonna shoot!'. . . . There was a big rifle all cocked and ready to shoot. I'm just from my outfit, I was coming here to get something to eat. And he said, `I think you're a Jap. Just come with me." After that incident, McCabe was accompanied by a non-Navajo at all times.

On the eve of the First Marine Division's departure for the island of Okinawa, which was expected to be the bloodiest landing of the Pacific War thus far, the Navajos performed a sacred ceremonial dance that invoked their deities' blessings and protection for themselves and their fellow Americans. They prayed that their enemies' resistance might prove weak and ineffectual. Some of their non-Indian buddies, standing on the sidelines, scoffed at the whole idea. When Ernie Pyle, the famed Scripps-Howard war correspondent, reported the story afterward, he noted that the landings on Okinawa beach had indeed proved much easier than had been anticipated and noted that several of the Navajos were quick to point this out to the skeptics in their units.

Farther inland, however, Japanese resistance stiffened, almost slowing the American advance to a halt. As might be expected, a Navajo was asked by another Marine with whom he shared a foxhole what he thought of his prayers now. 'This,' the Navajo replied, 'is completely different. We only prayed for help during the landings.'

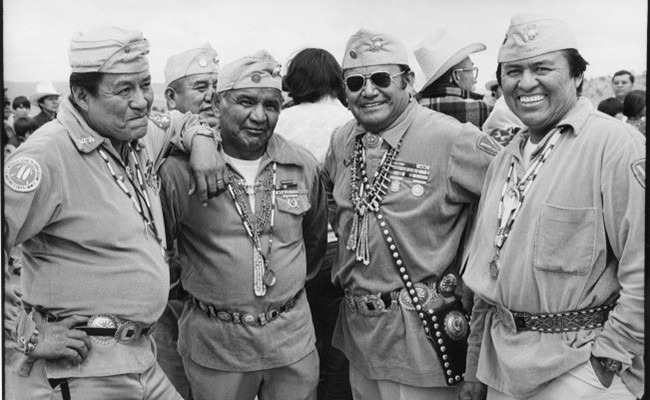

Eventually, Navajo code talkers served with all six Marine divisions in the Pacific and with Marine Raider and parachute units as well. Praise for their work became lavish and virtually endless as they participated in major Marine assaults on the Solomons, the Marianas, Peleliu, and Iwo Jima.

Commenting on the Marines' Iwo Jima landing, Major Howard Conner, the Fifth Marine Division's Signal Officer, said that 'The entire operation was directed by Navajo code. . . . During the two days that followed the initial landings I had six Navajo radio nets working around the clock. . . . They sent and received over 800 messages without an error. Were it not for the Navajo Code Talkers, the Marines never would have taken Iwo Jima.'

On an August evening in 1945, the Navajos were, quite naturally, among the first to receive the news that everyone had been waiting to hear. After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki three days later, Emperor Hirohito had urged the Japanese nation to 'endure the unendurable' of surrender. The war was over.

In all, 421 Navajos had completed wartime training at Camp Pendleton's code talker school, and most had been assigned to combat units overseas. Following Japan's formal surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, several code talkers volunteered for duty with U.S. occupation forces in Japan. Others were sent to China for duty with American Marines there. One code talker, Willson Price, remained in the Marine Corps for thirty years, finally retiring in 1972.