On August 2nd, 1943, CBS War Correspondent Eric Sevareid and a small group of American diplomats and Chinese army officers climbed aboard a Curtiss C-46 Commando transport plane at a U.S. Army Air Forces base in Chabua, India. Sevareid wanted to report firsthand on an ongoing mission to get gasoline and other supplies to China in support of Chiang Kai-shek, whose forces were fighting the Japanese. The USAAF’s brand-new Air Transport Command had been struggling to run the most audacious and dangerous airlift operation ever attempted—flying “the Hump,” over the foothills of the Himalayas—and Sevareid wanted to report on the operation.

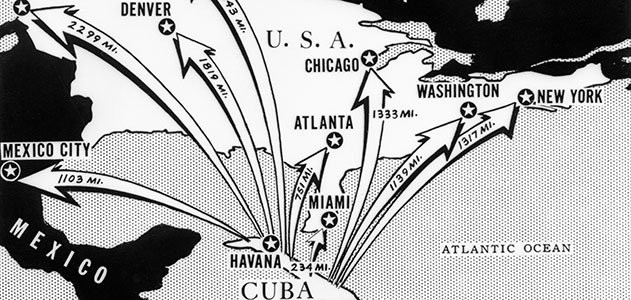

China had gone to war with Japan in 1937, but by the time the United States entered the Pacific War, Japan had sealed off China from any source of supply. Its ports had been conquered, and the last rail connection with the Soviet Union, a distant and pitiful lifeline, had been closed in 1941 by a Soviet-Japanese neutrality treaty. The infamous Burma Road lasted a while longer, but when the Japanese captured the port of Rangoon, the Burma Road was left with no supplies to carry.

Flying over Burma (today, Myanmar) - a 261,000-square-mile swath of mostly mountainous terrain the size of Texas—was the only way.

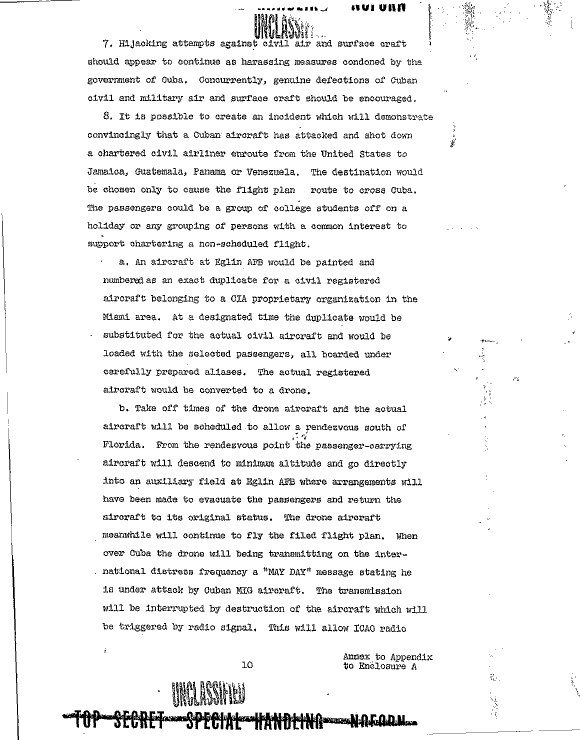

As the C-46 climbed high above the Patkoi Range, the aircraft that pilots had dubbed “the flying coffin” suddenly lost its left engine, and it soon became clear that the plane was going to crash. “I stood in the open door of that miserable Commando and declared, ‘Well, if nobody else is going to jump, I’ll jump,’” John Paton Davies, one of the American diplomats, later wrote. “Somebody had to break the ice.”

Sevareid followed Davies, but only after grabbing a bottle of Carew’s gin. He and 19 other men landed in the jungle—the C-46’s copilot did not survive—near a village that was home to a notorious tribe of headhunters, the Nagas, who, amazingly, hosted and fed them until help arrived 22 days later. Most likely because of the VIPs aboard the flight, intensive search-and-rescue efforts were mounted, including parachuting a flight surgeon to the marooned party. That was the beginning of serious search and rescue along the Hump routes. Before “the Sevareid flight,” crews and occasional passengers were pretty much on their own in the Burmese jungles and mountains.

On their 80-mile trek back to civilisation, a native guide explained the Hump to Sevareid in a way that perfectly encapsulated its astonishing expanse: “India there,” he said, pointing in one direction, and then, pointing in the other, “China there.”

The Second Sino-Japanese War occupied the attention of 1,250,000 Japanese troops stationed in Southeast Asia and China itself. It was a huge commitment by the Japanese, but they faced a Chinese force of more than three million. That Chinese army did little—the war had essentially become a stalemate—but was nonetheless a threat, and that meant those million and a quarter Japanese soldiers couldn’t be sent to Guadalcanal or anywhere else in the South Pacific. President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided that Chiang Kai-shek, the supreme commander of most of China’s army—Mao Zedong led the rest—was his guy, and Chiang needed American support.

Roosevelt imagined a superpower role for China after the war, and he wanted to be on good terms with the generalissimo. Chiang kept demanding more supplies, and Roosevelt kept sending them, at least until he became increasingly disenchanted with the Chinese Nationalist dictator.

But was that really the reason for flying some 500 to 560 miles over the Hump? To supply the Chinese and keep them in the war, thus pinning down all those Japanese troops? That has been the popular explanation for decades, but it is far from the whole story.

The Hump was a myth in many ways. Even the description “over the Himalayas” stretches the truth, for none of the several Hump routes overflew mountains that were technically part of the Himalayas. Yes, some of them crossed the Patkai and Santung Ranges, which forced a minimum cruising altitude of 15,000 feet, especially when flying by instruments in poor visibility, and that left no margin in the event of an engine failure in a twin-engine C-46 Commando or Douglas C-47 Skytrain or even a four-engine Consolidated C-87/C-109 Liberator Express. The Himalayas, though, were part of what percolated the extreme weather and jetstream-strength winds that were the routes’ severest challenges.

The flood of memoirs, war stories, and reminiscences from members of the Hump Pilots Association (some 5,000 at its peak) was unequaled among such postwar alumni groups, and its annual conventions seemed to increase the significance of the feats they reported. “Every time we meet,” one former Hump pilot recalled, “the Himalaya Mountains get higher, the weather gets worse, and there are more Japanese fighters in the sky than there were in the whole fleet.”

The men who flew the Hump were near the bottom of the Army Air Force food chain; indeed, ATC, the abbreviation for Air Transport Command, was often said to mean “Allergic to Combat” or “Army of Terrified Copilots.” Those terrified copilots got little respect during the war but made sure the world heard about their exploits afterward. Inevitably, some of what they broadcast was myth and much was exaggeration. That said, they operated overloaded airplanes, some of them mechanically flawed and poorly maintained with no source of spares, and did it in the world’s worst instrument-flying weather.

Westerly winds sometimes reached 150 miles an hour (typically inflated by pilots in later years to 200 and even 250), and 115 miles an hour was not unusual. A trip in a C-47 from China back to India could see ground speeds of 30 miles an hour, according to some Hump reminiscences, and pilots cruising at 16,000 feet might find their aircraft carried uncontrollably to 28,000 feet, then suddenly back down to 6,000. The weather was at its worst from February to April, with fierce thunderstorms and heavy icing. May to September was monsoon season with even worse thunderstorms. October and November meant good weather, which brought out Japanese fighter planes, and December and January brought heavy winds, turbulence, and icing.

It didn’t help that Hump route charts were outdated and inaccurate, with many exaggerated height callouts. Some Hump pilots went to their graves believing they had seen a mysterious mountain taller than Everest—a peak of 32,000 feet looming far above them when they suddenly broke out of clouds into the clear. Sometimes the media were responsible for the exaggeration, for journalists everywhere knew that if they needed colourful copy, all they had to do was sign on for a Hump run.

IN THE EARLIEST DAYS OF THE HUMP, before Pearl Harbor, the route was flown not by the U.S. military but by an airline: CNAC, the China National Aviation Corporation, a cooperative endeavour between the Chinese government and Pan American Airways. Its pilots—mostly expatriate Americans and Brits flying Douglas DC-3s, some of them U.S.-provided—were the best mountain pilots in the Far East, and their skill and experience showed when the Army Air Force Ferry Command (ATC’s predecessor) began to fly the route in 1942. CNAC aircraft often carried more than double the tonnage that their Army Air Forces partners felt safe hauling aboard identical aircraft. The experienced CNAC pilots initially made flying the Hump look easy, but nobody yet realised that future operations would be flown by ill-trained newbies with no mountain- or weather-flying hours.

The Ferry Command’s early pilots were also skilful, though they lacked relevant experience flying over such terrain or in such weather. The first 100 were airline pilots who held AAF Reserve commissions. But when Hump tonnage began to build and a substantial fleet of cargo planes had arrived in India, the demand for pilots grew rapidly. AAF flight schools churned out as many as they could, but the best of them chose to fly fighters and fast medium bombers; for a new aviator in his early 20s, glory lay in combat, not in flying freight.

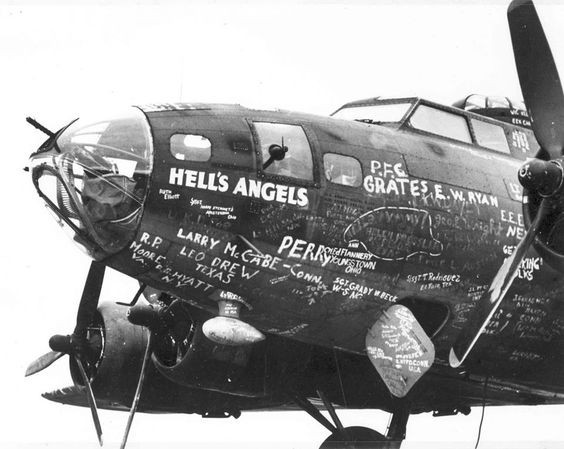

Despite the occasional presence of Japanese fighters, the Hump was officially declared a noncombat operation, with lower pay scales and more demanding rotation-home criteria. The Hump transports were easy but only occasional prey, since Japanese fighters would have to spend time, effort, and gas to find one airplane at a time. In October 1943, the Japanese stationed a swarm of Nakajima Ki-43 Oscars at Myitkyina (pronounced “Mitchinaw”) in northern Burma, tasked to interdict the Hump routes. This worked briefly—four Hump transports were downed—until Lieutenant General Claire Chennault, commander of the famous Flying Tigers, proposed launching a small group of up-gunned B-24s along one route. The Oscars found the Liberators and casually attacked, thinking they were unarmed C-87s, and eight of the Ki-43s were shot down.

Air Transport Command got the least capable flight students from the training classes; many arrived in India with minimal instrument–flying skills, some without multi-engine training. When possible, they were paired for training with airline pilots, many of whom were stunned by their lack of competence. By the end of 1942, 35 percent of the Hump operation’s new pilots showed up in India with just 27 weeks of flight training. During spring 1943, nearly a third of the AAF pilots force-fed to the China-Burma-India Theatre were only single-engine rated.

Even experienced crews got into trouble over the Hump. General Henry “Hap” Arnold was flying the Hump with a hand-picked crew aboard his personal Boeing B-17 in February 1943 when they turned a two-and-a-half-hour trip into a six-hour epic. Befuddled by lack of oxygen, the crew made enough navigation errors to put themselves over Japanese-held territory.

One small category of service pilots, however, were happy to log hours flying modified civilian airliners. After the war they would be at the head of the line leading to the door marked “Airline Captain,” even then a glamorous and well-paid job.

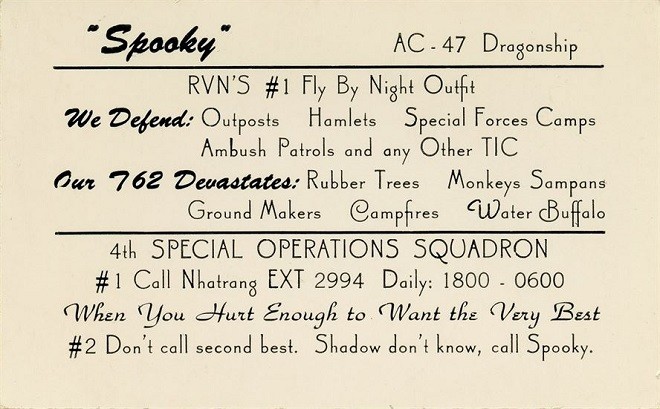

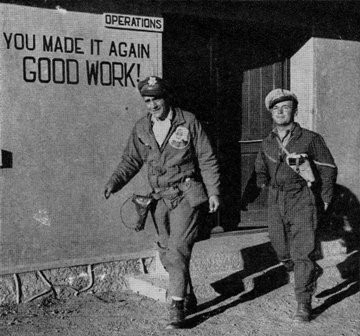

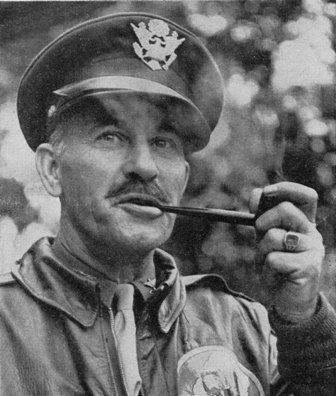

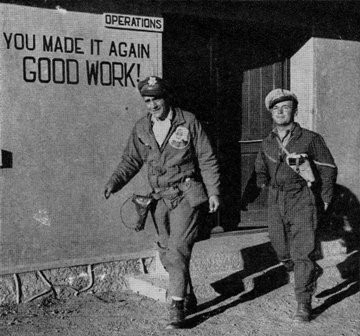

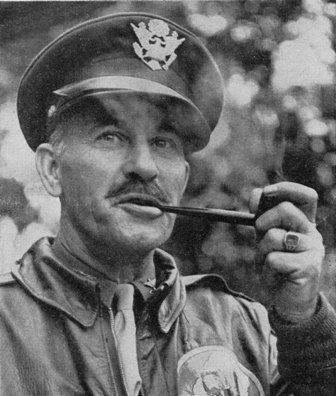

From its inception in early 1942 through the spring of 1943—the U.S.-run operation was what some likened to a civilian flying club run by its pilots. They decided when they would fly, what route they’d take, and how much cargo they’d carry. They were their own schedulers, dispatchers, and weather forecasters, and, not surprisingly, flights were often canceled because of bad weather or the threat of Japanese interception. That lasted until the arrival of Brigadier General Thomas Hardin, a former TWA vice president who took over the Hump command in August 1943. “From now on, there is no weather over the Hump,” he immediately decreed, telling the flying club pilots to suck it up or join the infantry.

Hardin flew the Hump, sometimes solo and regardless of the weather, in a worn-out North American B-25 medium bomber that he had somehow appropriated, and he arrived unannounced at the various ATC bases in India and China with his hair on fire, sacking and reassigning officers whenever he found laxity and incompetence. Hardin came to be feared and respected by the most aggressive of his pilots and hated by the malingerers. He asked more of his aircraft, maintainers, and crews than anyone had imagined was possible, and he was responsible for demanding and getting record tonnage delivered to China—first 10,000 tons a month, then almost 24,000.

Hardin was also responsible for a terrible Hump safety record; he admitted that setting new tonnage-delivered records was more important than bothersome safety procedures. During just one seven-month stretch during his tenure, there were 135 major accidents and 168 crew fatalities, half of them night-flying crashes. Hardin had initiated after-dark flying over the Hump, saying “airplanes don’t need to sleep.” At one point, every thousand tons flown into China cost three American lives. Hardin lasted just 13 months and was replaced by another brigadier general, William Tunner. Tunner would become famous as the orchestrator of the 1949 Berlin Airlift.

Under Hardin, Hump pilots were allowed to rotate home after logging 650 hours. A typical flight took about three hours in good weather, and some crews flew three missions a day in order to build hours as fast as they could, flying some 2,000 demanding hours a year—twice the amount that the Federal Aviation Administration today allows airline pilots to log annually. And, not surprisingly, tired crews crashed. Tunner changed the deal to 750 hours and a minimum of 10 months in theatre. Morale suffered some, since living in fetid accommodations at bases in India for almost a year was a cruel sentence, but safety improved.

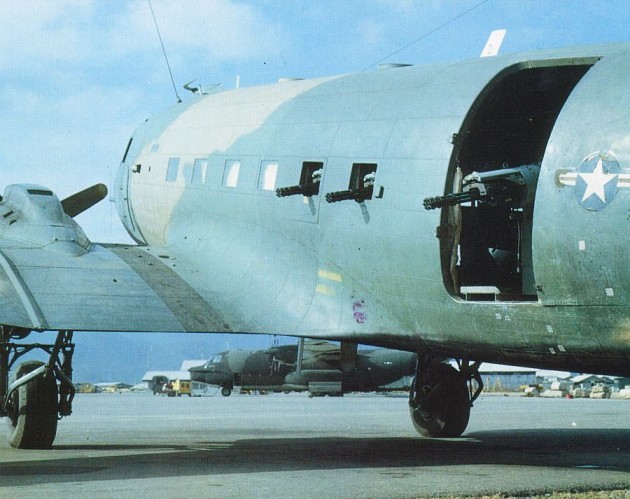

Initially there was the indomitable Douglas C-47/C-53, the two military versions of the DC-3. Pilots called it “the rocking chair of the air” because it was so easy to operate, but the early-1930s design had limitations. It was difficult to load with bulky cargo, struggled to reach operational Hump altitudes, and carried a relatively small load.

Along came the Curtiss C-46 Commando, a whale of an airplane that carried 70 percent more cargo than a C-47 and boasted two of the finest and most powerful piston aircraft engines ever produced: 2,000-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R2800 radials. The C-46 could munch mountains for breakfast, but it was deeply flawed. Still under development as a pressurised airliner, the military Commando was hastily sent to India when it should remained in testing. At one point, a group of early C-46s was returned with a list of more than 700 major and minor glitches that needed correcting before further production.

The C-46’s biggest fault was tiny leaks in wing fuel tanks and lines. Such leaks weren’t unusual among complex multi–engine airplanes, but in the Commando, they were fatal. Curtiss had failed to vent the juncture between wing and fuselage, so the gasoline pooled there instead of quickly evaporating. Random fuel-pump sparks caused 20 percent of all Hump C-46s to explode in flight. (Wing roots weren’t vented until after the war.)

In an attempt to turn a bomber into a cargo plane for the Hump routes, Consolidated Aircraft put a flat floor in its B-24, removed the guns and bomb racks, and called the result the C-87 Liberator Express. But the B-24 had been designed to carry a stable load in a small area on the airplane’s center of gravity: bombs in fixed, vertical bomb racks. When Hump crews flew C-87s randomly loaded with a variety of cargoes, few ever found a sweet spot where the airplane felt comfortable, stable, and in trim.

The army also tried to turn the B-24 into a Hump tanker, dubbed the C-109, with big flexible bags full of gasoline in the hold. It was difficult to land at the 6,000-foot-high airfields in China and soon acquired the name Cee-One-Oh-Boom. One C-109 blew a tire on landing, exploded, and wiped out three other Liberator Expresses. In his book Flying the Hump, ex-China-Burma-India pilot Otha C. Spencer wrote, “All the pilots on the base wished [it] had wrecked the whole fleet.”

It was the arrival of the Douglas C-54 Skymaster in February 1944 that turned the Hump operation into the largest, most efficient airline in the world. The Skymaster was the militarised version of the DC-4, the first large, four-engine American airliner, and it had the cargo volume of a railroad boxcar. The C-54 didn’t have the high-altitude performance to fly the “High Hump” routes, but in May 1944 British and American forces captured the Japanese fighter strip at Myitkyina, thus eliminating any opportunity for the Japanese to interdict the less extreme “Low Hump” routes. The C-54 did quite nicely at 12,000 feet and carried far more cargo per trip than even the porky Curtiss Commando. It was also safer than its four-engine predecessor, the Liberator Express, and its tanker version, whose accident rate was 500 percent higher than the C-54’s.

By early 1943, U.S. brass hats, including AAF chief Hap Arnold, were beginning to doubt the value of the Hump operation. Arnold felt the airlift could certainly be ramped up to accomplish what it had set out to do, but he saw little point in spending lives, material, and effort simply to sustain the will of the Chinese. Many felt that Chiang was husbanding his acquired supplies for use against Mao, not the Japanese.

That was a turning point for the Hump operation. Under the cover of aiding China, the ATC program quickly changed course to become the major source of supplies for the Twentieth Air Force, which was planning to bomb Japan with its B-29s from Chinese airbases. China had now become a launch pad, no longer of interest as a postwar partner. But ultimately, the Twentieth flew just nine Boeing B-29 missions from China against the Home Islands before it moved to huge airfields in the Marianas. The postwar Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that those few missions “did little to hasten the Japanese surrender or justify the lavish expenditures poured out on their behalf through a fantastically uneconomic and barely workable supply system.” For every four gallons of avgas delivered to the Twentieth, Hump transports burned three and a half.

Still, during 1944 the Hump flights grew exponentially in terms of tonnage, organisation, and operational sophistication. They became quite simply the world’s biggest international airline—750 aircraft and more than 4,400 pilots. Between August 1944 and October 1945, the Hump delivered almost 500,000 tons of material from India to China. Chiang got less than 20,000 tons of it—three pounds of every 100 that crossed the Hump. The Twentieth Air Force got gasoline and ordnance; Chiang all too often got wine, decorative shrubbery for his house, Ping-Pong tables, office supplies, condoms, and such.

Roosevelt died in April 1945, and his successor, Harry Truman, shared little of his warmth toward Chiang; nor did Truman believe that Nationalist China would play an important postwar role. China quickly became a decidedly minor player in Allied strategy. The Hump operation showed that a substantial amount of cargo could be airlifted anywhere, under the worst flying conditions, as long as those in charge were willing to pay the price in men, aircraft, and money. What it didn’t prove was that such an undertaking was useful. As a logistics operation, the Hump flights were a failure. The cost in aircraft and crews was enormous. Loss estimates vary between 468 and 600-plus airplanes (the AAF did not record every crash), but the best one seems to be 590 aircraft lost with 1,314 crewmen. General George C. Marshall felt the Hump had negative value: “The over-the-Hump airline has been bleeding us white in transport airplanes….The effort over the mountains of Burma bids fair to cost us an extra winter in the main theatre of war.”

In the end, the Hump had much to do with establishing the United States as the world’s airline leader. The War Department bought over 1,000 C-54s, 3,000 C-46s, and 10,000 C-47s—and many of them were sold as surplus to become American airliners after hostilities ended. The United States began the postwar period with the airplanes, the pilots, and the air-transport management skills to build a worldwide airline system, all developed at least in part by flying the Hump.